Within the field of political communications, the interplay of media narratives with public perceptions has long been a core focal point of study. Media narratives that sway public opinion can have a significant impact on the shaping of policies, outcomes, and the way history is recollected. Within this context, the tragic aftermath of the September 11th attacks and the sub-sequential Iraq War provide an interesting case study about these media narratives. This essay investigates how, in the wake of 9/11, language and rhetoric were used to otherize Muslims and those in Iraq, how this narrative of the other was cradled by media, and how this created a simplified, antithetical narrative which drew support for mobilization. Investigating this, it not only demonstrates how powerful media can be at molding public sentiment but also the ethical aspect of ensuring accurate information is disseminated during times of uncertainty and national tragedy.

The events of September 11th, 2001, commonly referred to as 9/11, marked a turning point in U.S. history and led to a heightened sense of vulnerability and fear. Not but 9 days after this tragic event, the Bush (2001) administration announced its War on Terror, stating:

“Our war on terror begins with Al Qaeda, but it does not end there. It will not end until every terrorist group of global reach has been found, stopped and defeated”. (paras. 45-46)

This war led the U.S. to have military involvement in several countries, including Afghanistan, Pakistan, Libya, Somalia, Syria, Yemen, and Iraq. Whether Iraq was involved in terrorist activities was widely debated among experts at the time, yet the declaration of the Iraq war from the U.S. received far-reaching domestic and international support. A poll from January 2002, found that if the U.S. decided to take military action in Iraq, 77% of U.S. citizens would be in favour, and another found 47% would be in favour even if Iraq had no involvement with 9/11 (Gallup/CNN/USA today in Bowman et al., 2008, NBC News/WSJ in Bowman et al., 2008). Although to this day, no direct link between 9/11 and Iraq has been found, the Bush administration’s claims of a link between Iraq and al-Qaeda led news media to perpetuate the narrative that Iraq was somehow involved in the attack.

At this time, the media landscape in the U.S. underwent a dramatic transformation, deeply affecting public discourse. Traditional news media [television, radio, newspapers] was the most dominant form of media at the time, with the cycle of 24-hour news having been already widely established for years. This allowed for a rapid dissemination of information among the public. Critics of such a media system often cite that this convenience can be dangerous to the “truth and accuracy” of media reporting (Rosenberg & Feldman, 2009, p.10). Much sensationalist media of the attack often later focused on the idea of other potential attacks on the U.S., evoking a reinforced fear of the event (Mitnik, 2017, p.12). It should be noted that islamophobia existed in the media before 9/11, with film and television often depicting terrorists as “one dimensional bad guys who were presumably bad because of their ethnic background on religious beliefs” (Alsultany, 2012, p.24). However, this type of media landscape saw an opportune state for islamophobia and attitudes that otherized Muslims to be further perpetuated due to the rapid dissemination of fear-based news media.

How did the other in Iraq emerge from rhetoric and language

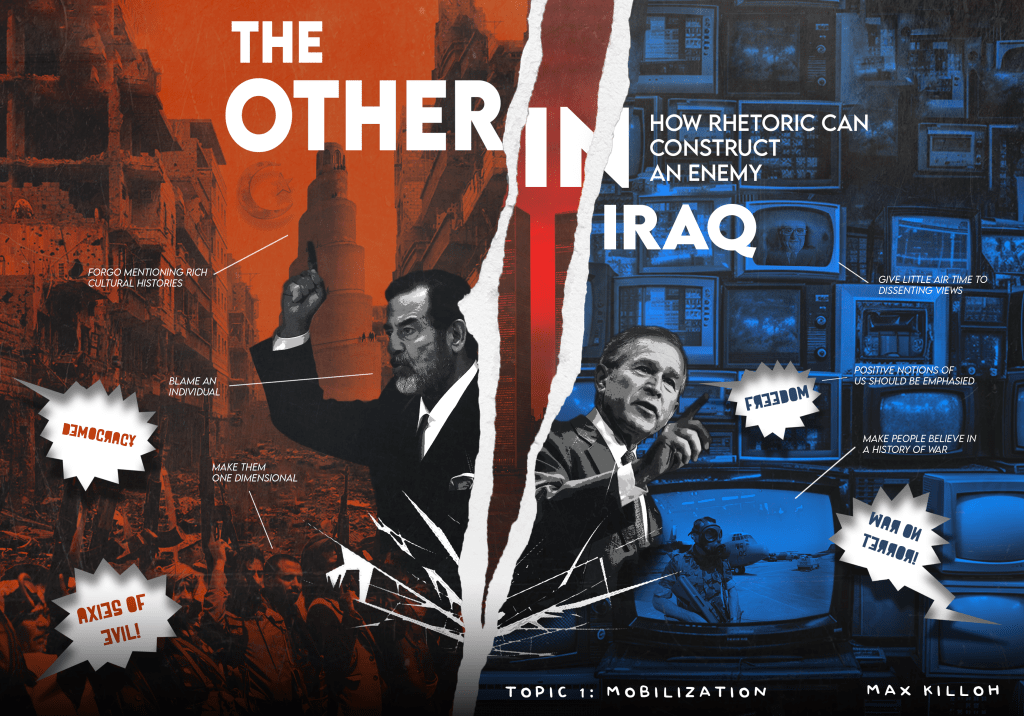

Post-9/11 saw an influx of media-speak and rhetoric which would seemingly create the idea of Iraqis and Muslims being the other in US media discourse. Vague terms such as the war on terror, or axis of evil were created by the Bush administration and often restated in media. Words like terror and evil present a narrative of danger, a narrative which seeks to show that there is an “orient other” [Muslims] who seeks to harm us (Awan, 2010, p.532).

These terms such as axis of evil are purposefully obscure and, in rhetoric, act as an empty signifier; an object whose meaning is empty and only filled depending on the context in which they are used (Laclau, 2005, p.131). These empty signifiers were restated by the media often within the context of Iraq and 9/11, helping to suggest the idea of a widespread, ever-expanding threat of terrorism, and that of a connection of the Saddam regime (Carruthers, 2011, p.38). This use of rhetoric is potentially where the otherizing of Iraq began. Since the U.S. began its involvement in the middle east, it could be said it often views itself as a global protector of democracy, a rather positive image to present. By attaching fearful rhetoric to Iraq, it helped to position Iraq not only as the other, but the U.S., being a global protector of democracy, as an ideological anthesis. It creates a narrative, that because Iraq is the other, it is the U.S.’s mission to defeat them, and bring them to them adopt democracy and westernized ideology (Huntington, 2011, p.21).

How the narrative of the other in Iraq was used by media.

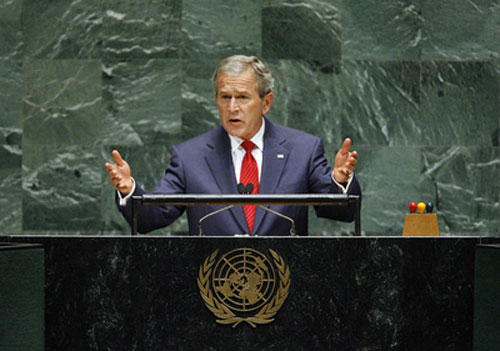

Once this antithetical narrative of the U.S. and the terrorist other had been established in rhetoric, it was used by the media to mobilize support for the invasion of Iraq. Van Dijk (1998, p.245) suggests the theory of the ideological square; where positive information about us is emphasized, and the negative is suppressed; positive information about them is suppressed, and the negative emphasized. In the lead-up to the Iraq war, the Bush administration emphasized positive notions about the U.S. such as the idea of promoting democracy, American values, and resilience in the face of 9/11: for example, Bush’s 2002 State of the Union address used the word “freedom” at least 14 times (Bush, 2002). Regarding de-emphasizing negative aspects of the U.S., dissenting views regarding U.S. foreign policy, the disruption of civil liberties, or experts who challenged the idea of pre-emptive war with Iraq, such as Hans Blix, Kofi Annan, or Scott Ritter, were often given little attention from media. It is likely to assume these issues were downplayed in media in the interest of national unity after the September 11th tragedy, as ideological opinions may have further or negative implications for the media outlets who give attention to them (Van Dijk, 1998, p.245).

Information about Iraq before the war was generally not emphasized or deemphasized on purpose by higher levels of government, instead one might blame the sensationalism of the 24-hour news cycle. Positive information about Iraq, such as its rich cultural history as one of the oldest civilizations on earth, was not often discussed by the media as a reason to not invoke military action. Doing so may have resulted in the U.S. public perceiving themselves as having a barbarian image (Alexander et al., 2005, p.30-31). Instead, the media focus regarding Iraq was often on Saddam Hussein personally (Althaus & Largio, 2004, p.796) and his potential link to 9/11, causing the country to be conflated in the public’s mind with that of the dictator. Media also frequently drew comparisons to the Gulf War and Iraq’s history of conflict with the U.S., likely causing greater acceptance of such a narrative due to this perceived history of conflict (Schafer, 1997, p.824). In this way, the media further cradled the us and them narrative presented by the Bush administration under the guise of assuring national unity in the wake of tragedy.

How this narrative simplified the narrative of 9/11 and the Iraq war

The power of this narrative of the other, conflated with 9/11, had in shaping public opinion towards the Iraq war can be seen reflected in available polling data from this period. A key argument used by the Bush administration in its justification for the war in Iraq was that there was a stockpiling of weapons of mass destruction [WMDs] and a collating with terrorists by Iraq; therefore, invasion is warranted under the overarching war on terror. A report in April of 2005 from the CIA detailed that no evidence of WMDs was found in Iraq (Duelfer, 2005, p.6-7). For many, this did not change the narrative that Iraq was a part of the war on terror, as two months after these findings were published, 61% of Americans believed the Iraq invasion to be a part of the War on Terror (Bowman et al., 2008, p.32). Furthermore, between 9/11 and the start of the Iraq war, many Americans indicated in polling that when presented with the option to blame Saddam Hussein for the attacks of September 11th, they chose to (Althaus & Largio, 2004, p797). This narrative of the other and the reasonably fast mobilization for support of the impending war allowed for an oversimplified narrative that Iraq was involved in 9/11 to emerge. This narrative would easily explain to the public why the Iraq war was occurring, despite this not being factually accurate. This punctuates the importance for media to address misconceptions when they arise, rather than neglecting them or choosing to underreport under the guise of assuring unity, as it will likely allow for the further proliferation of misconstrued narratives.

In the aftermath of the attacks of September 11th, a simplistic narrative of the other was created through rhetoric, propped up by news media to become a narrative of us versus them, which led many to believe the war with Iraq was done in virtuous retribution or protection of global peace. This essay explored the power of such a narrative through Iraq’s broad entanglement in the war on terror through widespread misconceptions of its involvement with 9/11. This case study demonstrates the delicate role of media following a national disaster, and how the need to create unity can be inadvertently highjacked to create false narratives which promote mobilization. While media cannot be definitively blamed for its role in this, it does raise questions about the ethical implications of the media’s ability to shape public discourse.

References

Click to open reference list

Alexander, M. G., Levin, S., & Henry, P. J. (2005). Image Theory, Social Identity, and Social Dominance: Structural Characteristics and Individual Motives Underlying International Images. Political Psychology, 26(1), 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2005.00408.x

Alsultany, E. (2012). Arabs and Muslims in the Media: Race and Representation After 9/11. New York University Press. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/canterbury/detail.action?docID=1002907

Althaus, S. L., & Largio, D. M. (2004). When Osama Became Saddam: Origins and Consequences of the Change in America’s Public Enemy #1. PS: Political Science & Politics, 37(4), 795–799. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096504045172

Awan, M. S. (2010). Global Terror and the Rise of Xenophobia/Islamophobia: An Analysis of American Cultural Production since September 11. Islamic Studies, 49(4), 521–537.

Bowman, K. H., Foster, A., O’Keefe, B., Weiner, T. J., Billet, M., Pinjuv, J., Benz, J., Beien, J., Clemens, A., Anderson, M., Blom, B., Schmitt, K., Lipson, E., Jun, M., Taylor, T., Rocha, A., Richeson, B., Jones, A., Fox, R., … Samadi, N. (2008). America and the War on Terror (p. 169). American Enterprise Institution. https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/america-and-the-war-on-terror/

Bush, G. W. (2001, September 20). President Bush Addresses the Nation [Congressional Address]. https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/nation/specials/attacked/transcripts/bushaddress_092001.html

Bush, G. W. (2002, January 29). President Delivers State of the Union Address [President’s State of the Union Address]. https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2002/01/20020129-11.html

Carruthers, S. (2011). The Media at War. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/canterbury/detail.action?docID=4762972

Duelfer, C. (2005). Comprehensive Report of the Special Advisor to the DCI on Iraq’s WMD, with Addendums (Duelfer Report) (Volume 1; p. 453). Central Intelligence Agency. https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/GPO-DUELFERREPORT

Huntington, S. (2011). The Clash of Civilizations and the remaking of World Order (Simon&Schuster hardcover ed). Simon & Schuster.

Laclau, E. (2005). On Populist Reason. Verso.

Mitnik, Z. S. (2017). Post-9/11 Media Coverage of Terrorism [John Jay College of Criminal Justice]. https://academicworks.cuny.edu/jj_etds/9

Rosenberg, H., & Feldman, C. S. (2009). No Time to Think: The Menace of Media Speed and the 24-Hour News Cycle. Bloomsbury Academic & Professional. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/canterbury/detail.action?docID=601536

Schafer, M. (1997). Images and Policy Preferences. Political Psychology, 18(4), 813–829. https://doi.org/10.1111/0162-895X.00080

van Dijk, T. A. (1998). Ideology: A Multidisciplinary Approach. SAGE Publications, Limited. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/canterbury/detail.action?docID=1024022

Leave a comment