Historically extremists in all corners of the political spectrum have long used propaganda and disinformation to further their agendas. Prior to the advent of the internet, television or long-wave radio, this information was often spread through physical means such as print, or socially through word of mouth. However, with the rise of the internet, actors from many corners have found a powerful tool to spread their messages. Online platforms, while being an integral part of interconnecting the world and making information accessible to the masses, have also become a breeding ground for these extremist groups to manipulate online conversations and spread mal/misinformation. The impact of these groups and individuals on digital literacy and online conversations is significant and warrants attention from policymakers, educators, and the public at large. It should be noted that while dis/mis and mal-information refer to separate ideas (Media Defence, 2022, p.117), this paper uses the term ‘disinformation’ as a cover-all term for these topics unless explicitly stated.

Extremist groups use a variety of tactics to spread disinformation and mal/misinformation on online platforms. Primarily these tactics include the creation of fake news, conspiracy theories, and the purposeful misrepresentation of information and data. However, more complex measure such as the use of bots and fake accounts to amplify messages, and the manipulation of online conversations by taking advantage of echo chambers and filter bubbles. These tactics allow extremist groups to spread their propaganda and gain followers, often targeting vulnerable individuals who are susceptible to their messages. The influence of extremist groups on digital literacy is also concerning. They manipulate digital literacy in order to spread their messages and create confusion and mistrust in the media. This can lead to a lack of critical thinking and the inability to distinguish between fact and fiction, further degrading an individual’s digital literacy ability. As a result, individuals may be more susceptible to extremist propaganda and may struggle to engage in informed conversations online.

It is clear that extremist groups are a significant actor in spreading disinformation to further their own agendas. This essay will examine multiple tactics used by extremist groups to spread disinformation, the impact of this on digital literacy and online conversations, and the responsibility of online platforms and governments to address extremist propaganda online. It is imperative that action is taken to prevent the spread of extremist propaganda and ensure that individuals are equipped with the necessary tools to engage in informed conversations online.

Tactics Employed by Extremists

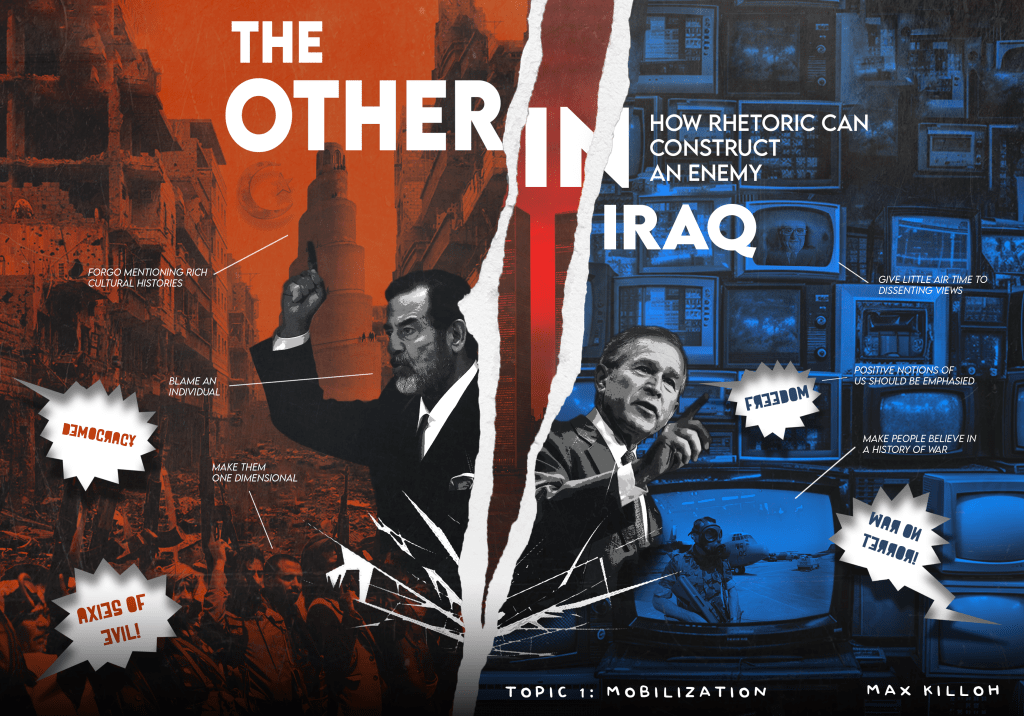

Extremist groups use various methods to spread disinformation on online platforms. These may include, the creation of disinformation media such as fake news stories and manipulated images and videos, they may also use bots and fake accounts to amplify said media and it’s messages (CISA, 2022; Southern Poverty Law Center, 2022). Some extremist groups often employ provocative and offensive content to elicit an emotional response from their audience. For example, The Islamic State of Iraq and Syria [ISIS] used social media to propagate lies about its military capabilities and successes, while also publishing graphic videos and imagery depicting violence and executions. This disinformation was used to gain support for the extremist movement and confuse or demoralize its enemies (Awan, 2017). While such tactics are not new to warfare, the use of social media to recruit individuals to an extremist cause is a relatively modern development. As a result of disinformation campaign, many foreign-citizens from around the globe whom supported the extremist group, we convinced to move to the region assist in fighting (Awan, 2017). Although blatant and provocative, this disinformation strategy worked for them. For westerners, and those not involved in the Muslim world, such a concept may seem farfetched as to why an individual could be persuaded to fight through digital radicalization. However, in recent years, comparable radicalization campaigns such as those from QAnon and other conspiratorial movements could be seen as similar. The important question to ask in this context, is why did they work so well?

Why it works – The manipulation of media literacy

A common tactic in recent forms of extremist disinformation is to manipulate readers into thinking that they are gaining a stronger level of media literacy when in fact they are degrading it. One way in which this is an evident tactic is the message which came out of the QAnon movement and had been perpetuated by conspiracy theorists for decades, calling for individuals to ‘do your own research’. This type of statement itself is rooted in the idea that institutions which discern information to public cannot be trusted, and that only you, as an individual can be the one to make up your mind when presented with information, weather it is factually accurate or not. The problem with this type of statement is that it not only does it perpetuate distrust in institutions, but it contributes to a self-sealing environment, where evidence from a trusted institution for a conspiracy theory not existing, is now is seen as evidence of there being a conspiracy (Lewandowsky & Cook, 2020, p.7). This promotes confirmation bias, and a belief that more value should be placed on non-institutional information sources such as blogs, and fringe forums/publishing. As this trust has now been placed on non-legitimate sources, the unaware readers level of actual digital literacy has now been degraded (Killoh, 2021, p.4).

The largest confounding factor to the tactical spread of disinformation is that communities who already have a low level of digital media literacy are exploited using the aforementioned tactic. The QAnon conspiracy theory was first disseminated through fringe online forums such as 4chan, 8chan [now 8kun] and various semipolitical right leaning subreddits. While one may expect such large conspiracies to have greater initial reach, it is important to remember that they all have a particular location in which they begin. These particular forums due to their fringe nature already had an abundance of conspiratorial ideas and theories on them. As those who believe in one or more conspiracy theories are much more likely to believe in others (Killoh, 2021; Swire et al., 2017), so it’s important to realise that whoever started the QAnon conspiracy had like chosen these specific forums as they already played host to similar ideas. It was a purposeful action to use the existing institutional distrust in these communities, to create more distrust through the manipulation of readers digital literacy levels.

The purpose of this type of manipulation is convince individuals to replace their trust of traditional institutions with that of digital and non-legitimate sources. As a result, affected individuals may be more likely to be involved in digital echo-chambers, where they will have pre-existing beliefs reinforced and will be limited in their exposure to diverse viewpoints. Rather unfortunately, what starts as a simple statement of ‘do your own research’, can be an effective propaganda piece to create a cycle of distrust where individuals may be more susceptible to extremist propaganda and less likely to engage in critical thinking and fact-checking. It is crucial to address these tactics and the exploitation of low levels of digital literacy, along with the role of echo chambers in the spread of extremist propaganda. As through this, we can ensure that individuals are equipped with the necessary tools to not be influenced by these tactics online.

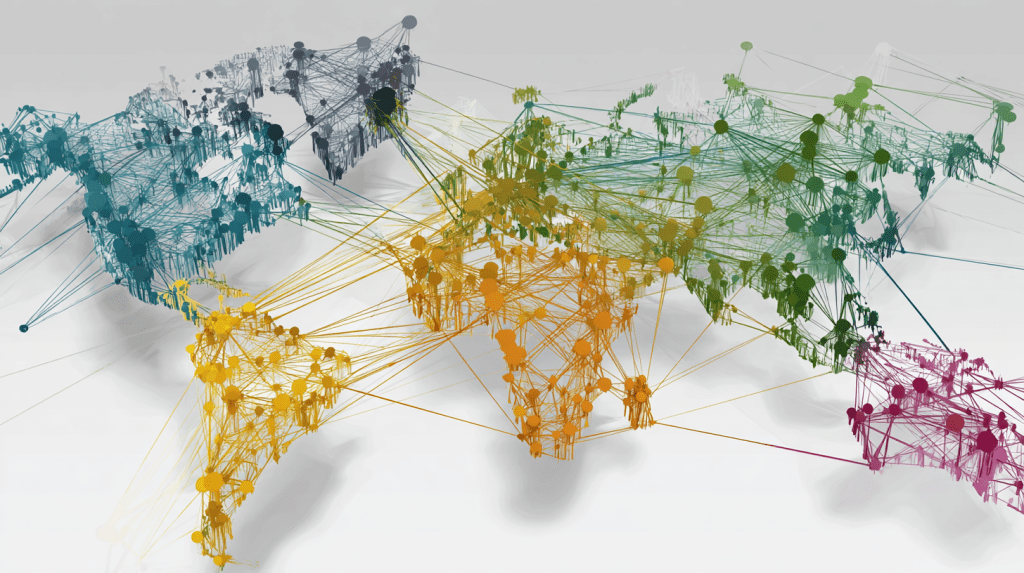

The use of bots in creating division

Extremist groups have been using bot accounts and fake personas to manipulate online conversations for years, creating an illusion of wide support and amplifying their messages. These tactics help to drown out opposing viewpoints and produce a false sense of consensus, and their use has become more sophisticated over time. For example, in 2016, the Russian based Internet Research Agency [IRA], used bot accounts to spread disinformation and manipulate conversations around the 2016 U.S. presidential election (Howard et al., 2019). They created fake social media accounts on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram, and were programmed to amplify particular messages and hashtags. Often when extremist groups attempt to manipulate online conversations in this way, a particular focus is placed on controversial issues to encourage division. These bots amplified both left and right leaning messages, some of which included #BlackLivesMatter, #ImWithHer, as well as #MAGA, and #HillaryForPrison (Howard et al., 2019, p.27). The purpose of this was create the illusion of widespread support for ideas in order to help produce divisions in the U.S. political landscape and assist in creating digital echo chambers to help further create a breakdown of trust in the U.S.

The impact of online discourse being manipulated by bot accounts is difficult to measure. Some claim that this particular tactic employed by the IRA may have caused enough distrust in the election to sway public opinion and affect the election outcome (Mayer, 2018). While it is unlikely that we will ever know the true impact that this tactic had on the election, it is obvious that the sewing of distrust and promotion of polarization has had real world impacts for the U.S. and opened doors to larger hot-button issues to be contested. It is essential to address the use of bots and fake accounts by extremist groups to manipulate online conversations and the impact of manipulated conversations on public opinion to promote informed decision-making and a healthy online discourse.

What is the solution?

Online platforms have a responsibility to remove extremist content and prevent the spread of disinformation and manipulation. By removing extremist content, online platforms can limit the reach of extremist groups and prevent the amplification of their messages. YouTube is one platform which in recent years has taken these steps, in 2019 in announced it would be taking more proactive steps to remove content relating to white supremacy and neo-Nazism. Specifically they developed a content moderation system to identify and remove this content in a more efficient manner than before, and has added measures such as reducing the visibility of content which has been identified to content of spread false information (YouTube, 2019). However, the role of governments in regulating extremist groups online is also crucial, as governments can enforce laws and regulations to prevent the spread of hate speech and extremist propaganda. In 2018, Germany adopted the German Network Enforcement act [NetzDG], requiring social media platforms with more than 2 million users to remove illegal content, including hate speech within 24 hours of a user complaint (Bundesministerium der Justiz, 2017). Not removing the content in this time frame means that the platform may face a fine of up to 50 million euros. While the law has been controversial, it has seen to be effective at reducing neo-Nazi propaganda and disinformation online.

Additionally, media literacy education is an important tool in combating extremist disinformation and manipulation, as individuals who are equipped with critical thinking skills and media literacy can better navigate online conversations and identify false information. MediaWise is one example of many programs designed to improve digital media literacy. It’s aim is to teach teenagers to debunk online misinformation and utilize fact-checking through interactive workshops and social media campaigns (Poynter, 2023). 82% of those who have taken part in the program have stated they felt more confident in their own ability to identify and debunk disinformation online (Tina Dyakon, 2020). Policymakers could consider making similar programs compulsory in school curriculums in order to help improve overall digital media literacy. By promoting media literacy education, individuals can become more resilient to extremist propaganda and misinformation, and better engage in informed conversations online. It is important for all stakeholders, at all levels, including online platforms, governments, and educational institutions, to work together to combat the spread of extremist disinformation and manipulation online.

In conclusion, the tactics employed by bad actors such as extremist groups to spread disinformation, have become increasingly sophisticated and effective, leading to the radicalization of individuals and the manipulation of public discourse. By creating and amplifying fake news and images, using bots and fake accounts, and exploiting low levels of digital media literacy, these groups have been able to gain support and sow division among the public. The manipulation of digital media literacy, in particular, is a troubling tactic, as it not only perpetuates distrust in legitimate sources of information but also promotes confirmation bias and limits individuals’ exposure to diverse viewpoints. To address these tactics, it is essential to promote media literacy, encourage critical thinking, and combat the echo chambers that reinforce extremist beliefs. Additionally, tech companies must take responsibility and implement measures to detect and remove disinformation and extremist content. The collective sense of vigilance and action towards disinformation is necessary to be adopted in order prevent the amplification of hate speech and the polarization of political discourse online. Only by institutions working together collectively, can the spread of disinformation and extremist propaganda be prevented, so that a more informed and tolerant society can be promoted.

References

Open for References

Awan, I. (2017). Cyber-Extremism: Isis and the Power of Social Media. Society, 54(2), 138–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-017-0114-0

Bundesministerium der Justiz. (2017). Netzwerkdurchsetzungsgesetz. Bundesministerium der Justiz. https://www.bmj.de/DE/Themen/FokusThemen/NetzDG/NetzDG_EN_node.html

CISA. (2022, October 18). Tactics of Disinformation [Government]. Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency. https://www.cisa.gov/resources-tools/resources/tactics-disinformation

Howard, P., Ganesh, B., Liotsiou, D., Kelly, J., & François, C. (2019). The IRA, Social Media and Political Polarization in the United States, 2012-2018. U.S. Senate Documents. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/senatedocs/1

Killoh, M. (2021). Trust Online. Unpublished Manuscript, University of Canterbury

Lewandowsky, S., & Cook, J. (2020). The Conspiracy Theory Handbook. http://sks.to/conspiracy

Mayer, J. (2018, September 24). How Russia Helped Swing the Election for Trump. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/10/01/how-russia-helped-to-swing-the-election-for-trump

Media Defence. (2022). Summary Modules on Digital Rights and Freedom of Expression Online in sub-Saharan Africa (p. 152). Media Defence. https://www.mediadefence.org/ereader/publications/introductory-modules-on-digital-rights-and-freedom-of-expression-online/

Poynter. (2023). MediaWise. https://www.poynter.org/mediawise/

Southern Poverty Law Center. (2022). How Extremists Spread Disinformation. Southern Poverty Law Center. https://www.splcenter.org/sites/default/files/election-disinformation-fact-sheet.pdf

Swire, B., Berinsky, A. J., Lewandowsky, S., & Ecker, U. K. H. (2017). Processing political misinformation: Comprehending the Trump phenomenon. Royal Society Open Science, 4(3), 160802. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.160802

Tina Dyakon. (2020, December 14). Poynter’s MediaWise training significantly increases people’s ability to detect disinformation, new Stanford study finds—Poynter. Poynter. https://www.poynter.org/fact-checking/2020/poynters-mediawise-training-significantly-increases-peoples-ability-to-detect-disinformation-new-stanford-study-finds/

YouTube. (2019, June 5). Our ongoing work to tackle hate. Youtube Official Blog. https://blog.youtube/news-and-events/our-ongoing-work-to-tackle-hate/

Leave a comment